Tying Together Common Syndromes

“Taking A Step Back From The Microscope”

- Chronic Back Spasms

- Facet Syndrome

- Maignes Syndrome

- Piriformis Syndrome

- Hip Impingement Syndrome

- Hip Flexor Syndrome

- IT Band Syndrome

- Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

These are a few of the musculoskeletal syndromes you’ve probably encountered in your readings about syndromes that plague runners and other distance athletes. These syndromes can affect areas surrounding the hips, back, knees and groin leading to massive cuts of mileage, pace and enjoyment of the sport.

In this article I’m going to take you through a very effective, yet not mainstream (for whatever reason) type of rehab for syndromes and your other aches and pains that you thought were just “age” or “overuse” related.

How can we address all of them with the same rehab? Simple, find the intersecting biomechanical points of inception.

In other words, where did they all start?

These syndromes are very common in triathletes, marathoners, and distance runners who’ve challenged their bodies to some degree within their training. It’s not just a veteran issue either Tons of beginners drop off the wagon annually with running-related injuries. One estimation is 60-90% of runners experience an injury annually. (USAF Marathon, 2018) The syndromes mentioned above top this list.

If you’ve been thinking, “Maybe I’m too old to run” or “I’m not one of the ‘lucky’ ones,” this article will enlighten and inspire you!

Will I go over rehab and treatment for all of these syndromes? No, but if you’re looking for my general recommendations, much of what I do to assist my distance athletes to improve can be found laid out, step-by-step, in my free online course.

I’m not sure exactly who coined the term “syndrome” surrounding these musculoskeletal conditions, but when we look at the body as a whole unit, rather than microscopic regions of pathology, the path to resolution is actually very simple.

The reason we complicate it so much in the first place is the fact that both healthcare providers and patients tend to look at the body in chunks or regions.

– Hip Specialists

– Ankle Specialists

– Podiatrists

– Back Specialists

We need to consider the entire body. If we don’t we are just patchworking together a rotten beam when really the main issue is the whole house has degrees of wood rot from top to bottom/ front to back.

Syndromes are a cluster of symptoms that seem to go together, but not always. In this article, I’ll be covering what I call the “Syndrome Syndrome,” in other words, what do all of these syndromes have in common (most of the time).

I remember the last time I saw a movie about a superhero who was stronger, faster, and more powerful than an average man. The hero wore a suit of red, blue and gold that has been the costume of choice for many children since the 1950s.

If you guessed Superman, you’re wrong. I was thinking Wonder Woman!

Although they’re different superheroes, they do have something in common. If we traced back their history, we’d surely find the intersecting line in both of their histories. Syndromes affecting runners and triathletes will also have an intersection point… the syndrome is just a successful, yet painful, adaption the body has made because of the environment, volume, habits, postures, and loads it has encountered chronically.

Let me say that again, syndromes are adaptations to the circumstance you’ve encountered and continue to encounter. However, despite your body’s seamingly “successful” adaptation, your training and progress is adversely affected. In other words, syndromes set you back rather than propel you forward.

Adaptations are not always favorable as a long-term adaptive strategy. An example of an adaptive response that’s great short-term, but not long term is sneezing. The pollen was the stimulus and sneeze is a great adaptive response, but sneezing daily would be a true pain in the ass.

The body is in constant adaption. The longer you rest, the more the body will adapt to rest. If we’re to recover optimally from the poor adaptation that yielded your syndrome, then we’ll need to reverse engineer the process to stimulate a favorable adaptation. This is what a good doc and coach will do in rehab. If they are crappy then they may just patchwork you back together, put you on the road, and wait for you to acquire the next stage of adaptation which is another syndrome, in the same or different area of your body. And this is how the Syndrome Syndrome starts… ongoing poor adaptation to milage.

Going back to that superhero analogy, symptoms of a syndrome also blend with other conditions. Many runners that I’ve had the pleasure of assisting, come in already convinced they have a single syndrome, just as you were convinced about Superman.

Looking through a microscope will make most people miss the large issues at hand. I’ve done this myself as I’ve encountered syndromes in my own personal health. I was blinded by being too emotionally close to the problem. I couldn’t see the big picture. I too had to see another healthcare provider to get some direction.

The intention of this article is to inspire you to take a step back from what you believe to be true about your syndrome and see where the intersecting lines of all of your aches, pains, syndromes and aliments start. Looking too closing into the microscope for each condition will blind you to the intersection points.

Is it nice to know everything that Dr. Google says about your syndromes?

Yes, but don’t get too stuck on the minutiae.

As a clinician, I understand the desire of patients to KNOW what they HAVE but it’s important to understand that a syndrome develops as a multifactorial process; it’s like trying to pinpoint only one reason why the New England Patriots win year after year.

There are hundreds of sports shows on TV discussing the multifactorial reasons why the Patriots win. This is why they can fill 2 weeks worth of football analysis before the Superbowl! There are also multiple variables on why your piriformis muscles are so tight… to find a solution we need to ask ourselves WHY.

Now I’m no football analyst, but I think we should all take a step back from the microscope for a moment to look at general themes. Taking a step back from your syndrome provides much more clarity and longer lasting results of treatment.

I’ve worked in clinical practice for 10 years, I’ve encountered countless syndromes. I’ve discussed each at length with other clinicians and here are 5 things I’ve learned. I’ll go over each in turn.

- Syndromes Don’t Occur In Isolation. They Come In Clusters.

- People With Syndromes Often Have A Common Presentation

- People With A Syndrome Look At It Through A Microscope

- Syndromes Often Resolve Better Long-term By Reverse Engineering The Development Process

- Rehabilitation Of A Syndrome Starts By Meeting Each Person Where They Are At

#1 Syndromes Don’t Occur In Isolation. They Come In Clusters.

I got a chance to take radiology (x-rays etc.) classes throughout grad school, and they had a rule about abnormalities coming in clusters.

When you see one large fracture, you should also be looking for smaller ones. Don’t let the large one sticking out the skin distract you.

When you see a tumor (life-threatening or not), you should be looking for more.

However, in our education about musculoskeletal syndromes, we ignored this foundational principle. Why? I have no idea, but after working with many people in clinical practice, I started to observe that syndromes also came in clusters.

If you have piriformis syndrome, you probably have chronic tightness of the iliopsoas (hip flexor muscle).

If you have have hip flexor syndrome, you probably have some signs of hip impingement syndrome (pinching groin pain).

If you have have Hip Impingement Syndrome, you probably have Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (Runner’s knee).

Honestly, odds are you have grades of all of the aforementioned if we inspected deeply.

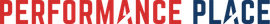

Why? I’ll get into that in the next section where we go through signs you can look for. I’ve also drawn a picture (one of a kind!) that describes the injury process and how all of these syndromes can present in clusters, especially in distance athlete populations.

#2 People With Syndromes Often Have A Common Presentation

I’ve made this drawing to demonstrate the classic presentation.

When considering biomechanical forces (posture, positions and loads) surrounding the onset of a syndrome, it’s actually very easy to identify the telltale signs that a runner is placing excessive loads and demands upon the region of their syndrome.

If the reason for your syndrome is biomechanical in origin, there are 5 easy ways to identify signs you can look for. The great part about having one of these 5 signs is that it means we can reverse engineer the process that created the syndrome. With the proper guidance, you’ll more than likely get back to feeling good and running hard within a matter of months.

– “Open Scissors” Torso

– Sway Back

– Pronounced Lower Rib Flare

– Chest Rises And Falls With Breaths

– Stretching, Massage, And Foam Rolling Are All Unsuccessful As Treatments

Why are these signs indications of a syndrome mechanism of injury?

Let’s go into each independently, but make sure to look at the arrows on the drawing as well because you’ll get more from these snippets when you see it from the broad scope.

“Open Scissors” Torso

Look at this open pair of scissors on this guy. The borders of the sharp parts are on the top part of the pelvis and lower part of rib cage. In the following image, look at that guy in comparison. See how the ribcage and the pelvis runs parallel to each other?

Athletes who are able to keep their “scissors closed” typically have spent time learning the skill. Keeping your “scissors closed” isn’t a genetic or age-related skill. It’s a skill you get to learn and retain through performing the drills that are recommended to you.

If you’re running with open scissors, all you may need is the addition of a few “closing” exercises or drills within your routine. Often times I see athletes who have many of the 5 syndrome signs have simply holes in their programming. No biggie. It’s not a character flaw. They too can build a body that can resist syndrome mechanics.

Living your life with many of the 5 syndrome signs often times lead to maladaptive movement patterns, which can load muscles, tendons, and joints beyond their tolerance points. What comes next? You Google a bit… lo and behold, you slap yourself with the label of a syndrome.

Sway Back

Have you seen a horse that looks like it’s been ridden too much?

Don’t be confused by the presence of large glutes for a sway back when looking for this sign. You can have large butt glutes and not have a sway back, but it seems that social media culture (selfies) have combined glutes and sway back as a combined motion. Look at any group of ladies posing for an Instagram picture before hitting the town in downtown San Diego and you’ll see what I mean.

As a general rule, I never suggest selfies… if they don’t lead to a syndrome then they certainly will result in people unfollowing you. Self portraits are fine but that’s a whole other story for another day.

Yes the open scissors torso is basically the same presentation, but we are now looking at the backside of the athlete rather than the torso as a whole. It’s an easier way to identify a sign of poor stabilization systems for athletic performance. We will go into the reasons a sway back can contribute to a syndrome development when we discuss sign #4.

Sway back often times appears more prevalent in fatigued states of training as we hit threshold. A good way to combat this is to be able to recognize when it’s occurring and attempt to correct it by verbal cueing. Some people are able to identify and correct it on their own and some others require a coach’s assistance. If you can’t correct it, I would recover a bit and then push towards it again. Think threshold or FARTLEK to train for improved posture and supportive systems during your running.

People who have had a past disc injury (flexion intolerant) oftentimes have a sway back appearance years after the disc issue has resolved. This is a maladapted posture. The body is in constant adaption. Avoidance of a painful motion in flexion intolerant cases (rounding the spine) oftentimes forces the person to acquire a maladapted lower back arch, which will further create a cascade of events that lead to the syndromes of the lower body.

Pronounced Lower Rib Flare

This lady pushing the sled was not the example I wanted to use but royalty free images are hard to come by. However, it is an excellent example of undesirable lower rib flare in sport. Sled pushing is not very different from sprinting. When we dial running back to what it fundamentally is then this example actually becomes pretty relevant.

Running is a moving plank. Being able to “plank/ lean into the sled” and keep the legs moving is basically running. The inability to keep balance in that forward lean leads to the upper torso leaning backwards to compensate for an unstable forward lean. This creates that “open scissors” posture we already covered and destabilizes the body, again exposing tonic muscles to overload and development of a syndrome. We will cover tonic muscles fully later in this article.

As a side note, using a sled to retrain a solid forward lean without exposing the lower ribs is a great training tool.

Chest Rises And Falls With Breaths

Chest breathing is a very easy way to identify the beginning process of a syndrome. Upward motion of the shoulder, rising of the chest wall and hollowing of the belly are often associated with people with poor intra-abdominal pressure. Adequate intra-abdominal pressure is required to create a fixed centerpoint for propulsion of the body to move forward.

Generically we can say the “core” is weak in chest breathers, but overall I think call this region “the core” does not do it justice. Most of the lay public’s understanding of the “core” is very much lacking. If you’d like to go down this rabbit hole, read this article I wrote about “real core training.”

Continuing down the breathing pathway conversation, upward motion of the shoulder and chest with a deep breath mechanically destabilizes the abdominal cavity, leading to power leaks in human motion.

How? Great question.

The concept of proper breathing has floated around the athletic professional world more since 2015 despite having been observed and theorized many years prior. Most athletes who’ve developed an abdominal injury have probably had a conversation about “core strength” with their rehab professional at some point (if they’ve kept up with their research, anyway).

Proper breathing and the resulting intra-abdominal pressure is the FOUNDATION for a healthy core during any athletic movement. By the way, core strength has nothing to do with injury prevention! That’s more dependent on ENDURANCE, ie: the ability to hold the optimal posture for the duration of the movement.

Breathing is important not only for oxygen intake, but also for stabilization of the torso and pelvis when performing an athletic motion. This protects the obliques from becoming overworked and strained. Hear me out:

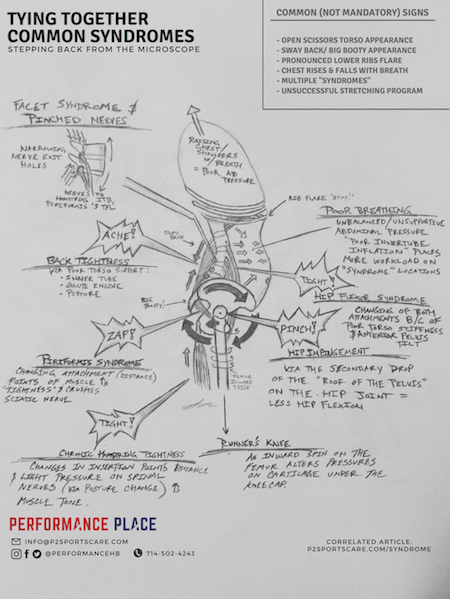

The diaphragm (the parachute-like muscles inside your torso) has two functions:

– Primary Function: bringing in oxygen

– Secondary Function: stabilization of the torso

This parachute flattens downward creating negative pressure in the thoracic (chest) cavity. This negative pressure creates a vacuum that sucks in the air you need to survive.

Secondarily, the flattening effect compresses on the water and organ-filled cavity beneath it, which helps stiffen your belly/back region via an outward-pushing pressure. This pressure is maintained via the entire abdominal wall (front, back, and sides) as well as the pelvic floor.

Stiffening of this region is what allows you to transfer power and force from the ground to your body. Without it, you’d look like Gumby running: sloppy, not very powerful and asking a whole heck of a lot from your “tonic/ syndrome other muscles to do the work of the entire internal pressure system.

Stretching, Massage, And Foam Rolling Are All Unsuccessful As Treatments

This one is a pretty common complaint from syndrome people actually. They will often seek care at a facility like mine because they’ve tried all of the typical things people try. Stretching, rolling, and massage are at the top of the list.

When we get into the section about tonic versus phasic muscle groups and characteristics, it will begin to make sense why these typical solutions don’t solve the problem. As of now, just know you’re not alone and this is very common. Only the simple problems are resolved with simple solutions.

#3 People With A Syndrome Look At It Through A Microscope

I’ve found in clinical practice that it’s very hard for people who are being personally affected by a syndrome to see the big picture. With conditions that have structure-centered names, like Piriformis Syndrome and Facet Syndrome, people tend to focus on the muscles, tendons and joints as the cause…not the effect.

I get it, I really do. Muscles, bones and tendons are more relatable to people because they can touch them, see them and feel them. Mechanical processes are like understanding how a clock can keep its time. It’s more complex than simply identifying the hands of the clock.

The drawing in this article was made specifically to address this problem so we can start reverse engineering the adaptive process that created the syndrome in the first place. As you can see a many of the syndromes I’ll be addressing in this article are identified on the image. Please look at the image a few times as you read through the sections identifying the biomechanical process/ big picture of your syndrome.

#4 Syndromes Often Resolve Better Long-term By Reverse Engineering The Development Process

A strong majority of the time it starts with the QUALITY of your body’s stable points (except in trauma cases). How well is your body creating fixed points to produce motion FROM?

Your body has two groups of muscle-based musculoskeletal stabilization, tonic and phasic. When they are both used at the same time we don’t just benefit from having double the support. It actually increases exponentially by a concept of co-contraction that also produces compressive support.

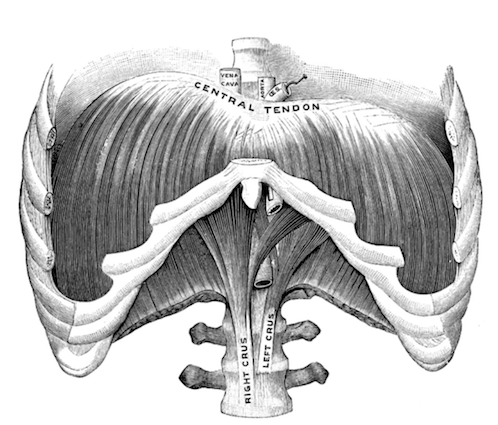

The concept of co-contraction can be simplified with a basic Jenga and Duct Tape analogy.

Imagine a stack of Jenga blocks with Duct Tape on one side. Wouldn’t it be more stable if we use tape on the other three sides?

The duct tape in this analogy refers to the muscles of the sides of the spine and other joints.

If I was talking about the torso, these wrap all the way around the torso and support the spine (and any joint for that matter) via a muscular loop. The floor and top of the muscular loop is also important with providing stabilization via compression.

Think of that Jenga stack again. It’d be harder to push a block out if someone were to step on it, right?

Building your ability to contract all sides of the abdominal wall and hold this desired position for a desired task, and for the appropriate time (endurance) is key. When considering other joints (the shoulder, knee, hip and ankle) co-contraction will always create compression across the joint and it will be stabilizating to that joint.

Going back to the tonic and phasic muscles groups, both are great at what they do but just like two different sprinters, they have different temperments and attributes. To have complete stabilization for reduction of a syndrome, we need to have both systems functioning in harmony. They are both part of the same team and support each other when needed.

When they aren’t working in unison is when our syndromes occur. Allow me to explain…

Let’s start with learning the traits of each group. Just like a 5k runner and 100m sprinter, both are an important part of the school’s track team.

Tonic muscles are the ones that typically become tight in cross syndrome, like lower and upper cross as described in Janda’s works. These are the ones people will typically say they need stretched or massaged to feel better. Janda believed tonic muscles are primarily involved in posture.

Tonic muscles have mainly slow twitch muscles fibers, which have more mitochondria (the powerhouses of cells) than fast twitch fibers, therefore they have greater endurance. This equates to their ability to support the body through prolonged exercises and postures longer than the phasic group.

Phasic muscles are the opposite; they’re the ones people forget about until a trainer or healthcare provider brings them up. Phasic muscles are composed of more fast twitch muscle fibers and therefore are powerful by natural composition. The tradeoff is that they often fatigue quicker than tonic muscles because they also hold less mitochondria.

Trainers will often tell you that your “X” muscle is “off”, but in truth, it’s not really off, it just fatigues quicker than the others. Janda believed these muscles to have the primary function of movement. Pavel Kolar expanded on Janda’s “posture versus movement” concept by adding that both groups need to work in unison to create high quality movement. Stabilization precedes movement.

Dr. Richard Ulm DC expanded further upon this by recognition of the Extension/Compression Stabilization Strategy (ECSS), as it pertains to weightlifting. In a nutshell, he says our compensated movements, found within our Functional Gap, are due to the phasic group giving out and the tonic group still holding on for dear life. This ECSS is where the tonic muscle group is providing inefficient stabilization that roots itself deeply in our development and neurology. In endurance sports we see the same thing occur, but instead of lifting heavy weights we are propelling our bodies forward.

All of the muscles that “feel tight” are typically tonic muscles. They fatigue later than the phasic muscles. The theory of why this happens is deeply rooted within our human development.

I’ll make it as simple as I can: our brain connects to the tonic group first during our development so that connection is stronger. When your form begins to degrade during movement (weightlifting, running, swimming, etc), this is when the tonic group takes over and still has some gas left in the tank but they also get overused and can become affected by the syndromes you have been reading about.

Tonic Muscles above the waist:

Upper Trapezius

Pectoralis Major

Pectoralis Minor

Biceps

Scalenes

Subscapularis

Sternocleidomastoid

Muscles of Mastication (chewing)

Forearm Flexors

Tonic Muscles below the waist:

Iliopsoas (Hip Flexor)

Rectus Femoris

Tensor Fascia Latae (TFL)

Piriformis

Hamstrings

Calf Group

Tonic Muscles around the “core”:

Lumbar Spinal erectors

Cervical Spinal erectors

Quadratus Lumborum

Do any of the listed muscle feel tight on you? Many deconditioned people claim more than half of the list.

On to the phasic, “inhibited” group…

Phasic Muscles above the waist:

Middle and Lower Trapezius

Rhomboids

Deep Neck Flexors

Triceps

Deep Core

Deltoids

Forearm extensors

Phasic Muscles below the waist:

Gluteus muscle group

Vastus medialis (inner quad)

Vastus lateralis (outer quad)

Tibialis anterior

Peroneals

Toe extensors

Phasic Muscles around the “core”:

Mid-back Spinal erectors

Rectus abdominis

Have you been told by a therapist, doctor, trainer or website that one or many of these muscles could be the key to your pain, performance or training program? Many people with pain in the hip or back have been told to “turn on their glutes,” and people with shoulder pain are told to “activate their lower trap, middle trap and serratus anterior.” Sound familiar?

What they are attempting to do is to build the harmonious system where all of the muscles share the workload, all of the joints are positioned well within their places (joint centration) and stacking patterns of the musculoskeletal system allow for the proper distribution so we don’t overload one region creating a syndrome.

How can you form this harmony? That’s a topic that is well beyond this article. I have courses available that address this based upon some of the conditions I see frequently. Some of the info is free and the best stuff you’ll have to pay for… but if you’ve enjoyed this article it will be money well spent!

Now that we know how each group works, let’s reverse engineer a few syndrome pathways…

#5 Rehabilitation Of A Syndrome Starts By Meeting Each Person Where They Are At

This is one of the things that took me the longest to learn in assisting patients to the correct treatments for their syndrome. I was hard-headed and arrogant. I knew that I knew what was “right” for their syndrome recovery, but the problem was that I didn’t know what was right for the person at that point in their life.

The solution to your problems will come to you when you’re ready to receive it.

Forcing ideas of ditching massage, Active Release, rest, and injections come when the person is ready. I’ve indirectly turned away many patients with musculoskeletal syndromes because I simply failed to hear what they were telling me.

“I want you to do ART on my piriformis.”

“My massage therapist said you should stretch my hip flexors and strengthen my glutes.”

“I’m looking for a new doctor and XYZ was working, can you do that for me?”

Looking back, my answer should have been always in agreeance rather than a long-winded educational conversation about how my treatment will be better than what they directly said they wanted.

How I would help you recover from your syndrome is irrelevant unless you’re ready to hear it because if you’re not receptive of the information, you’ll find someone else to do the treatment protocols you are dead set on.

To be clear, I don’t want you to take this as me trying to belittle patients and saying that I’m so great and knowledgeable… That couldn’t be further from the truth. Understanding where you are at in your understanding of your syndrome is critical in my recommendations for recovery. Just like teaching a person of any age to hit a baseball, my teaching plan would depend on what skill sets they start with when I meet them.

My intention by writing this article and drawing this infographic is to help more people who enter a sport rehab clinic take a step back from the microscope of a syndrome and the misdirection that type of mentality creates.

Is there any research surrounding this viewpoint of syndromes?

During the process of creating this graphic for the public to better understand my theory, I began to get asked by other clinicians about “the evidence.” To that I said “great question”… so here we go!

To frame this well from the start, I can say with certainty that my point of view hasn’t been all tied together in a nice little bow and handed to us through research validation, but it has been in sections or regions. My purpose is to logically bring the parts together so we can stop looking at syndromes from a narrow, microscope-based view.

Let me lay out what I believe occurs in the non-trauma development of the syndromes:

- Central stability diminishes via one, or many of the supporting systems (solid ground contact, abdominal co-contraction or intra-abdominal pressure) not being utilized (multifactorial causes)

- Decreased torso resiliency creates increased load on tonic muscles to keep us upright (Janda’s work)

- Unequal sharing of load (bodyweight and more) amongst supportive systems leads to maladapted postures and motions

- The anterior aspect of the torso “opens” creating rib cage flare and anterior pelvic tilt

- On the lower extremity, the acetabular rim drops, creating hip impingement and/ or labral pathology

- The femur internally rotates to create abnormal patellofemoral contact points under the patella, creating local knee pain

The compensation path continues downward to ground contacts in the foot, which creates altered forces distribution back up the chain (chicken or egg here)

Let’s speak locally now about each syndrome and how these mechanics can create symptoms of that syndrome… I’ll include some research references here as well for the nerds.

Chronic Back Spasms

Is reverse engineering rehab the only way to reduce pain or discomfort associated with syndromes?

No, there are many ways to manage and modify pain but pain management is only one part of the puzzle. We offer soft tissue care and joint mobilization in our facility just like most other sports rehab facilities and people love it.

To keep them in control of their own recovery, I tell my patients this:

“Soft tissue work can help you, but it’s only 25% of the puzzle and should be implemented in certain phases in your reverse engineering process. It’s also a crutch many people lean on for years. Don’t get stuck in this rehab purgatory. Reverse engineering the syndrome process will lessen the need for deep tissue work and manual therapy over the long term.”

Not every medical facility will agree with me on this. I strongly believe in this process and I also have the means to implement it. Understand that rehab facilities are also businesses. My facility is no different. In fact, I’m writing this article because I want you to come in to my facility or buy one of my eCourses. I’m not hiding that, but also I’m not going to suggest incomplete care because the other missing parts are not offered at my facility.

Some docs may not suggest more than deep tissue work because they don’t offer more than soft tissue work… I get it, I use to practice that way too. Addressing scar tissue and adhesions are an important part of recovery, but without building the supportive systems to unload the syndrome muscles, the syndrome will come back over and over again.

Frustrating right?

Back spasms, as pertaining to this biomechanical model, would fall under the category of Facet Syndrome, Maigne’s Syndrome, or a lumbar disc herniation (not within this article). Read these sections to learn more.

Facet Syndrome

Facet Syndrome Symptoms According To Dr. Google:

- Lower back pain or stiffness

- Lower back pain with twisting, bending or arching the spine

- Back pain when getting out of a car

- Difficulty standing up straight

- Pain cramping or weakness in the buttock region/ glutes

- Referral to the hips, groin or back of the thigh (not past the knee)

- Back pain when leaning backwards

- Loss of muscle flexibility

- Unpredictable and can reoccur through the year

In my opinion, this grouping of symptoms is really bad. Realllly bad!

This sounds more like a lumbar spine disc issue to me. I pulled these symptoms of Facet Syndrome from the top Google searches for “Facet Syndrome Symptoms.” If you’ve had these symptoms I think you should be looking at this article I wrote on back pain. In my past 10 years of practice I can count on one hand how many times I’ve diagnosed a person with these symptoms with Facet Syndrome. An incorrect diagnosis will yield an incorrect solution.

Let’s take a look into the biomechanical model of how true Facet Syndrome can occur (but don’t depend on Dr. Google for the symptoms because these are not great).

What the intersection point between Facet Syndrome and other syndromes in this article?

I’ll take this one from a mechanical point of view since it seems the most logical. Facet Syndrome has been dubbed a type of back pain that is extension intolerant. Based upon some of the conversations I’ve had with other back pain experts, we know that all structures in nature have a load capacity before deformity. Based on my experiences weightlifting, pain comes before deformity as a protective alarm. Unloading structures will allow the alarm to stop and allow the structures to desensitize.

Combining the McGill “guy wire” and Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization “intra-abdominal pressure” models, the supportive systems can assist in unloading the facets.

Observationally, these people often are living in lumbar extension. The will more than likely have a sway back, anterior tilt (ass out), and ribs popping like a firecracker appearance. See the sections above for the 5 signs of the Syndrome Syndrome.

One of the central concepts used in my lower cross theory is the effects of tension and compression on neural structures as presented by Michael Shacklock in his book “Clinical Neurodynamics.” Altered biomechanics within my drawing model can place abnormal stress and loads upon neurological and musculoskeletal structures. In the situations where I am proposing a nerve is being affected, please default to this concept of nerves.

First they don’t like to be stretch too far. In fact over 8% elongation of neural structures (spinal cord, plexuses, nerve roots and mixed nerves) we have observed diminished venous blood return. At 15% elongation, vein and artery function halts all together. This phenomena indicated that extra tension on a nerve can negatively affect its function. (Ogata et al. 1986) (Lundborg et al, 1973)

Again tension develops with elongation at a section, which can occur from actually being “overstretched” at that location or poor contributing adjacent nerve slide into the area of tension. This contributing slide will successfully reduce location tension under 8%, to keep a nerve happy. (Shacklock, 2005)

Compression can also cause restrictions of intraneural (inside the nerve) blood flow. Beyond 30-50 mmHg, research has shown reduction of nerve health in the form or less blood flow, conduction (potential to tell the muscles what to do) and axonal transport (sending material to the end of the nerve).

So nerve compression and elongation are bad?

Not at all. In fact, compression and elongation are normal occurrences within human motion. If you’re feeling achy, dull, stabbing, burning and numbness because of nerve compression or tension, it’s just that your neural structures are not at that moment to handle normal compressive and tension forces. That can be because of chronic exposure, past injuries, past joint immobilization, or other things that you should have gotten treatment for in the past yet self-resolved.

Syndromes fall within this list. They may seem like “non-injuries” but the process has a cumulative effect as you can see with neural compromise, which can affect the tone of muscles like the lumbar paraspinalis, quadratus lumborum, hamstrings, piriformis, hip flexors, and more.

How does this nerve concept tie into Facet Syndrome?

Compression can occur as the spinal nerve roots exit the spinal column, which can ultimately lead to tight muscles of the back causing back pain. Make sense logically?

Pain associated with Facet Syndrome is said to be “hard to localize” and “referred” because the sensation doesn’t follow a spinal nerve root. I don’t think the contributors of Wikipedia included superficial neurology through… which brings us to our first segway: Maignes Syndrome of the Lumbar Dorsal Ramus (skin nerves).

Maignes Syndrome (aka: Posterior ramus syndrome)

Maignes Syndrome Symptoms According To Dr. Google:

Maignes Syndrome has 4 characteristics for inclusion of the diagnosis:

- Trophic changes (discussed below) of the skin referred to as cellulalgia

- The patient will not feel pain at the correlating spinal level with facet palpation

- Advanced imaging is unremarkable

- Local injection into the correct facets seem to decrease symptoms (but it’s a hunt)

As we all know, nerve cells are not a bunch of cells, they’re one cell that has one very long arm at times. Maignes Syndrome classically won’t follow the exact distribution of a spinal nerve root but that doesn’t mean we won’t have mixed nerves as being the culprits.

The lumbar cluneal nerves are the terminal ends of lateral rami of the posterior rami of lumbar spinal nerves L1-3. Basically the cluneal nerves are parts of the L1-3 spinal nerve roots, so if the L1-3 spinal nerve roots are affected then the cluneal nerves would as well. This sounds like mixed dermatomes to me! Let’s go down this path.

Now we just to find out where the pressure on nerves (multiple nerve roots) or mixed nerves (cluneal nerves) is occuring at.

What the intersection point between Maignes Syndrome and other syndromes in this article?

Mechanically, lumbar extension will narrow the lumbar intervertebral foramina (holes in the spine where the nerve roots exits from). As the nerve roots (L1-3) exit from the spinal column, they pass through the bony tunnel of altering sizes based upon position. In theory, people with Maignes Syndrome would feel a relief of symptoms with even slight lumbar flexion (rounding) or spinal distraction (think drawn and quartered).

I don’t have proof of this, but I question if the trophic skin changes are present in non-Maignes Syndrome people. Could it be observed after clinical presentation? Could the skin changes be in fact, lumbosacral facial adaptive changes to decrease lumbar (low back) past flexion intolerance pain (last disc injury when it was painful to bend over). (Langevin et al. 2009)

Dr. Phillip Snell DC and Dr. Justin Dean DC observed that lifting of the local skin layer from the firmer layers decreased symptoms in 50% of Maignes Syndrome cases (observation at the moment) using skin rolling in an effort to decompress local cutaneous neurology. (Dermal Traction Method, 2018) Interesting right?

That begs the question of why the local skin deep nerves (cluneal nerves?) are sensitive. Pressure on the entire nerve root will sensitize the entire nerve since it is one cell. We see this in lower and upper extremity radiculopathy cases.

Would it be logical to look toward the spine and investigate the possibility of extension-based (or ipsilateral lateral bend) nerve root compression of the L1-3 nerve roots? I think so.

From a self-perpetuating cycle way of thinking, would it also be logical to consider that compromised nerves roots may create hypertonicity (or hypo) in the muscles of the low back, creating more extension of the lumbar spine and more compression of the nerve roots as they exit from the ever narrowing holes within the spine?

If you’re following along still, and on board with the idea that a nerve can control the tone (more or less) of muscles, then we should investigate that same theory with the next syndrome… Piriformis Syndrome.

Piriformis Syndrome

This is an extremely common, and in my personal opinion, overused diagnosis. I have seen more cases of “Piriformis Syndrome” enter my office that are successfully reduced with a simple change of lumbar spine position.

I’ll cover some factors later in this section on how to differentiate true and pseudo Piriformis Syndrome, but for now just think about some logic. If you’re piriformis, and/or leg pain, is reduced with a change that is not at the piriformis, or hip for that matter, is there a probability that the solution is not in the hip area?

If your doctor is not using differentiating factors within your examination to at least rule out the possibility of your buttock and leg pain being from a different region then they could be directing you to subpar solutions.

I know, I know, I probably sound like a know-it-all again… don’t confuse my passion with arrogance. I have found more incorrect Piriformis Syndrome diagnoses than I can count. My passion comes from the frustration and lack of examination I see from some rehab “experts.” Our job is to listen, thoroughly exam, diagnose, and recommend the correct care. Don’t let your doc jump to care too soon?!

When we finally get away from an incorrect Piriformis Syndrome diagnosis, you can get better with leaps and bounds. All it takes is the correct recommendations.

Piriformis Syndrome Symptoms According To Dr. Google:

- Single sided hip pain

- Worse with sitting or standing

- Better with walking or laying down

- Numbness to the lower parts of the extremity (back of the thigh, sometimes to the foot)

- Severe shooting

- Sometimes lower back pain

To dig deeper into the research, I was able to find a Systematic Review (Hopayian 2018) (level one research) for the most telling quartet of symptoms of Piriformis Syndrome:

- Buttock pain

- Pain aggravated with sitting

- External tenderness near the greater sciatic notch

- Pain with increased piriformis muscles tension

To me this sounds a whole heck of a lot like a lumbar (low back) nerve root irritation again, yet people may say, but there’s no back pain. You’re right. There doesn’t have to be back pain. I only learned this after questioning thousands of patients about their “Piriformis Syndrome” symptoms. Often times the discovery of related regions is left behind without taking a detailed history. Tightness, aches, stiff, “grumpy back” and pain are still indications of possible back relevance.

What’s the intersection point between Piriformis Syndrome and other syndromes in this article?

Looking at how this ties into my sketched model theory, we can see in the region noting “tightness of the back/ facet syndrome” the nerve roots can be come pressurized as they exit the spinal column. These nerve control tone/ tightness of the piriformis, tensor fascia lata (TFL, the hamstrings, the psoas and much more) Even light pressure (enough to occlude a vein) is enough to create nerve compromise in various ways.

Does it have to hurt when a nerve is compromised?

Not at all. Talk to people who have tingling on the side of the thigh (“Pseudo IT Band Syndrome) verse someone with sciatica who are in excruciating pain.

Can the piriformis be the cause of the leg issues? Maybe, but I wouldn’t bet my bank roll on it based upon what I’ve seen in clinical practice.

Not at all. Talk to people who have tingling on the side of the thigh (“Pseudo IT Band Syndrome) verses someone with sciatica who is in excruciating pain.

Can the piriformis be the cause of the leg issues? Maybe, but I wouldn’t bet my bank roll on it based upon what I’ve seen in clinical practice.

By looking at the sketch’s mechanics, there’s also another theory of how the piriformis could be so overused and tight (if it was confirmed to be the cause of leg symptoms via advanced imaging). Changing the distance of any muscle’s attachment points beyond “normal” would produce a protective stretch response and yield a “tight muscle.” If being held taut, the piriformis could compress the sciatic nerve as it passing under or through the muscle itself.

The drawn model represents the changing points, mostly by the inward femur rotation, that occurs as the phasic muscles of the body start to give up when reaching a state of fatigue. (See above section if you still need more info on tonic versus phasic muscles)

Now let’s consider the neural-based biomechanical possibility that could yield a tight piriformis muscle. The drawn model also shows an increased low back arch (extension), which couples with other syndromes (hip flexor, hip impingement, facet…). This will create pressure on a spinal nerve root that can alter the electrical impulse that controls all muscles in the hips and legs. Remember that neural response to stretch that we discussed in the Facet Syndrome section, this is what we are considering in this theory.

The piriformis could simply be an effect of altered electric “juice” telling the muscle to be chronically tight… leading to local tenderness, buttocks pain, pain with sitting, etc. This increase in muscle tone is just like what we went over in the Facet Syndrome section.

Is this truly piriformis syndrome? Are your symptoms driven by the piriformis tightness or are they driven by biomechanics pathways that compress the nerves that controlling the piriformis?

Chicken or egg huh? I’d suggest if we are looking at more than one syndrome we find that common intersection point to reverse engineer the whole process. Simple and then who really cares about what came first?

How can we be sure if we looking at true or pseudo piriformis syndrome?

With all other variables controlled (no ambient hip or extremity motion) can we reduce the symptoms?

Some things that have worked in my experiences are easily found by performing a Dynamic Slump’s Test.

Does cervical flexion (looking down) or extension (looking up) change buttock, leg or “piriformis symptoms”?

Does isolated lumbar flexion (rounded low back) or extension (arching backwards) modify the symptoms?

Does compressing the lumbar spine in a flexed or extended position change anything?

Does extending the opposite knee, ankle, foot and toes (“kicking out the leg” on the uninvolved side) reduce symptoms?

If the answer was yes in any of these, I would bet most of the money in my bank account that we are looking at lumbar (lower back region) nerve root irritation via a closing dysfunction of the intervertebral foramen or a disc issue or a nerve glide issue.

If you’re a member of the lay public reading this, you probably didn’t understanding that last line… It’s ok. You won’t need to. Read it to your doc and see what they think. Treatment protocol for a true piriformis syndrome vs. the other is very different so isolating down the plan of attack is critical in the beginning.

Since we are in the back side of pelvis region going over Piriformis Syndrome, now’s a perfect time to jump into the front side and see what happens as the femur rotates inward and the pelvis begins to rotate forward (anterior tilt).

Hip Impingement Syndrome

Hip Impingement Syndrome, aka Femoroacetabular Impingement is commonly misdiagnosed as Hip Flexor Syndrome, Hip Labral Tears and Hip Flexor Tendonitis. When we take a look into the symptoms and biomechanics you’ll find through a thorough examination and history-taking process that seperating of the conditions is very simple.

Hip Impingement Syndrome Symptoms According To Dr. Google:

- Common region of pain is the groin

- Person may also have low back, hip pain or both

- Loss of hip range of motion

- Sometimes coexisting with a hip labral tear

I’d agree with those symptoms but I’d also like to add the following:

- Pain sitting into a low chair

- Pinching pain when attempting to stretch the back of the hip (glutes), ie: pigeon stretch

- Worse with crossing legs

- Increases with more time sitting

- Stretching provides short term relief (in hours) before the discomfort returns

- Deep ache inside joint

- Better with changes of position, walking after sitting down for a while

- Person feels better to keep their hips wider (sitting unlady-like)

These are just a few of the symptoms I’ve heard frequently in my experiences (personal and clinical).

Patients with pain into the front of the hip will often come in saying they have hip flexor syndrome, or have been told they have a tight hip flexor (iliopsoas muscle). Their conviction of the “tight psoas” being the cause often times can distract a less experienced practitioner and lead to an inefficient care recommendation. Runners, triathletes and other distance athletes will often have been told by popular media, coaches or partners about the “tight hip flexor” being the problem and that stretching it is the answer.

Examination of hip is the simplest way to know for sure what the diagnosis really is, because with all of the symptoms noted above we still have these major diagnoses in play:

- Lumbar discogenic pain

- Lumbar nerve root irritation

- Cluneal nerve compression

- Hip Impingement Syndrome

- Hip Labral Tear

- Psoas Tendon Pathology

Passive hip testing is the best, if we aren’t looking to blow a few thousand dollars on an MRI Arthrogram (the gold standard image as of 2018). Here are the tests I like to use in combination with a thorough history:

- Dynamic Slump’s Test

- Scour’s Test

- Dynamic Scour’s Test

- FABER’s Test

- Dynamic FABER’s Test

- Axial Compression of the Hip

- Passive Hip Range of Motion

- Resisted Hip Ranges of Motion

- Rule out spine components as being a contributor (I use a McGill Style examine)

What’s the intersection point between Hip Impingement Syndrome and other syndromes in this article?

Biomechanically how does Hip Impingement Syndrome occur within the graphic? Where’s the intersection point?

Anterior pelvic tilt… and all of the spinal, hip and abdominal motions that go with anterior tilt.

In 2014, we found acetabular position (hip socket rim) had a profound effect on pain-free hip flexion in people suffering from hip impingement. Let me say that again in a simple way, if we can control the pelvis then we can control hip. Generally, a 10 degree reduction of anterior pelvic tilt decreased hip impingement symptoms with on average 5-9 degrees MORE of hip motion. The more posterior pelvic tilt, the more pain-free hip flexion people will have! (Ross et al. 2014)

How I implement this into my patient care are to reduce sensitivity triggers and build pelvic control coupled pain-free hip motion. Exercise suggestions would be a tangent to this article, so you can access them here if you want them.

Biomechanically, this is all tying together. Excessive lumbar extension (arching) will often have coupled anterior pelvic tilt. Already we have a common intersection point of the syndromes we covered: Piriformis Syndrome, Facet Syndrome, Maignes Syndrome, and Hip Impingement Syndrome.

I guess I’ll ruin the surprise for you now, this sloppy torso positioning is also the common intersection point for the syndromes we are going to cover next: Hip Flexor Syndrome and Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (Runner’s Knee).

Hip Flexor Syndrome

Hip Flexor Syndrome is a common “garbage can diagnosis” in my opinion (and in the opinion of many other rehab clinicians I know). This is an easy syndrome to throw at a wall to see if it sticks.

Many distance athletes with anterior hip pain will be told at least once, in their journey for the proper diagnosis, that they have Hip Flexor Syndrome. I personally hate to toss a “muscle-based” syndrome name at any athlete because it often narrows their attention to a muscle as needing to be stretched, rather than cleaning up biomechanics. Reverse engineering the biomechanics is a better long-term solution, rather than patch working your hip together on a daily basis.

If I had to estimate the percentage of patients I see who respond well to this model, I’d guess around 90%. I test my patients extensively before I suggest care, yet I’ve found it’s still an artform to figure out what type of corrective exercise cues the person will accept. Recommended exercises, cues and dosage are different for everyone it seems. There’s no single magical exercise that works for everyone.

I’ve seen people who’ve tried everything from manual therapy (massage, adjustments, trademarked tissue work) to injections and prolonged rest; most of them still tend to respond to a reverse engineering process.

Hip Flexor Syndrome Symptoms According To Dr. Google:

Commonly called hip flexor tendonitis, Snapping Hip Syndrome or Dancer’s hip, the common symptoms are:

- Cramping or clenching sensation of the upper thigh

- Upper leg feeling tender or sore

- Loss of strength on the front of the hip

- Tugging sensation on the front of the upper thigh

- Muscles spasms in the thigh or front of the hip

- Reduced hip range of motion

- Limping

- Inability to kick, sprint, jump, walk and perform gait related exercise

What’s the intersection point between Hip Flexor Syndrome and other syndromes in this article?

The hip flexor is primarily thought of as the muscle that flexes the hip because of the obvious name. When we get back to the actual name of the muscle (actually two muscles) in question, the iliopsoas muscle, the action of the muscle becomes less obvious. Perhaps the ambiguity is what we need since the hip flexor has the capacity to do much more than flex the hip when in open chain movement.

Muscles typically attach to two or more points. We call these origins and insertions in anatomy class, but which one actually moves is based upon which point is more stable/ fixed in place. If the spine (the origin) is more stable, then the hip will flex as a result.

If the spine is less stable, then the spine will move towards the other point of attachment of the iliopsoas. This produces lower back extension, rotation and lateral bend towards the same side… to follow along more with the 2D drawing let’s just say it extends (arches) the lower back.

Lastly, if both points are fixed to the same degree, then we have an isometric (no motion) contract that pairs with other muscles crossing the hip and pelvis to stabilize the joints. Co-contraction is always makes the regions between it more resilient to ambient motion. If isometric contractions didn’t happen then we would be more supple than Gumby and we wouldn’t be able to even stand upright.

Considering the same mechanical pathway we’ve used with all of the other syndromes so far, this low back arching can produce light spinal nerve root pressure of the nerves innervating, and ultimately controlling, the hip flexor group (L1-4), which in turn can create increased tone (the feeling of tightness).

So which comes first? The muscle tightness from overuse, the muscle tightness from nerve changes or biomechanical changes from poor torso endurance?

I’d love to say it’s the poor torso endurance but I really don’t have an answer to that question… I don’t think we ever will. In theory however, if we can improve posture and quality of movement with the correct exercise prescription, we can improve the ability of the low back to hold a non-arched position.

Wouldn’t we resolve both of the following issues?

- Less than optimal stable spinal iliopsoas origin point (aka sloppy spine)

- Increased nerve root pressure creating a hypertonic iliopsoas

I use this thought process when I create rehab programs in my clinic and they seem to work really well, even with little or no manual therapy!

Could I be affecting the body favorably in a different way? Sure, but my logic tells me that reverse engineering both of the possible causes from the common intersection point make the most sense. But hell I don’t know… I’m learning as I go too.

The last syndrome in the hip/ pelvis region is the infamous IT Band Syndrome.

IT Band Syndrome

I’ll start by saying that IT Band Syndrome is misdiagnosed often. The diagnosis seems to be tossed around as carelessly as a dollar in a casino.

Why is IT Band Syndrome over utilized as a diagnosis?

Many of these people actually have a lumbar spine radiculopathy instead. A strong majority of lay public I’ve encountered with self or clinician diagnosed IT Band Syndrome have L5 nerve root impingement actually. This is important to differentiate in the beginning of care because the starting point changes slightly, symptoms triggers are different and the pain modifying suggestion are different.

One of the simplest ways to separate these two diagnosis that overlap in symptomology is a detailed history taking. Here’s some of the common histories I hear that don’t match the diagnosis of IT Band Syndrome.

- If you don’t run, there’s a low chance your hip, knee, and thigh pain is from IT Band Syndrome.

- If you’re a weightlifter and wake up with thigh pain, there’s a low possibility your problem is IT Band Syndrome.

- If you experience change of skin sensations, there’s a low possibility your problem is IT Band Syndrome.

- If you don’t have the mileage to merit a chronic friction syndrome of the knee, there’s a low possibility your problem is IT Band Syndrome.

- If your thigh and knee pain is increased with sitting, there’s a low possibility your problem is IT Band Syndrome.

IT Band Syndrome Symptoms According To Dr. Google:

When we look into the common signs and symptoms of IT Band Syndrome, there’s often a lot of “muddy water.” There’s isn’t one sign that I can pick out that is a clear cut distinguishing symptom that means you have IT Band Syndrome. Some sources have started to narrow down the location of symptoms to the outer part of the knee, which is correct. Still many of the public I’ve encountered feel that symptoms on the outer part of the hip, to the outer thigh, and to the outer knee are classified as IT Band Syndrome, which is often very incorrect.

The correct IT Band Syndrome symptoms are the following:

- History meriting enough volume for a knee friction syndrome

- Activity must involve repeated knee flexion (probably without extra load/ weightlifting)

- Fluxuations of running volume recently

- Outer knee pain around the lateral femoral condyle

- Sharp stabbing quality with isolated knee bend around 30 degrees

- Local swelling around the outer knee without large temperature changes

- Local tenderness

- No changes of skin sensation

- No symptoms below the knee

- Advanced imaging should be clinically correlated

I’m not saying IT Band Syndrome doesn’t exist, but it’s not as common as you would think.

What’s the intersection point between IT Band Syndrome and other syndromes in this article?

The IT Band is a dense fibrous structure that is not intended to stretch, so don’t try or waste your time. The knee as a joint has been called the “circuit breaker of the leg;” when you have an issue there you need to inspect the surrounding regions (torso, hip, ankle, foot, and loading patterns) to stop it from occurring.

Can the IT Band Syndrome be overuse at the knee? Sure but let’s ask ourselves WHY. Reverse engineering is the key, remember!

Could it be excessive mileage?

Sure, but didn’t the other knee get subjected to the same amount of mileage?

Could it be an old injury?

Sure, but if not trauma based, what caused the past injury? Perhaps the IT Band Syndrome is just an adaptation to the past injury, on the same or opposite leg even… so can we reverse engineer that injury as well? Perhaps, if no permanent adaptations have occurred.

Could it be that your hips are too tight?

Sure but why are they tight again? One possibility is altered biomechanics or posture (see the main image graphic). The nerves of the spine control resting tone of all of the muscles of the body, so could the muscles be affected negatively somehow? I’d bank on that first honestly!

How does the biomechanical model presented account for IT Band Syndrome… great question. Let’s find that intersection point…

If we are looking at true IT Band Syndrome then we still can use the biomechanical model because it accounts for altered distal contacts of the IT Band as it crossing the knee joint, via the internal femoral rotation (from the hip).

If we looking at it from a neurogenic origin, then the L5 nerve root can be affected by light pressure as it exits a narrowed intervertebral foramen (hole in the spine) creating symptoms to the glutes, lateral thigh and lateral knee (around the area of true IT Band friction pain).

Moving away from the hip, let’s look further down at the knee as the femur often fails to hold position by eccentrically drifting into internal rotation, creating altered stresses under the kneecap yielding Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (Runner’s Knee).

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome, also known as Chondromalacia Patella and Runner’s Knee, is very common in the running and endurance sport world. At one point in my reading, one article cited that Chondromalacia Patella was the #1 reason for people to present with knee pain to their general practitioner.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome is often seen as a “wear and tear” type of condition that comes on slowly as athletes age. Many lay public feel there’s not much we can do about it since they have been told (or read) that it’s an “age-related” condition.

I’m of the belief that conditions often do progress with age, but it’s not really the age of the person we need to consider. Rather it’s the time that has past since the adaptation began that’s important. It’s like skin cancer… if you spend too much time in the sun without protection you’ll get it young. If you spend too much time moving in poor form when you’re young and active, then you’ll have the dreaded Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome at some point. Let’s not blame your age… it’s your habits over time. I’ll cover the biomechanical reasons why in a bit.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome Symptoms According To Dr. Google:

Classically, we have thought that a laterally tracking knee cap creates this syndrome because of the underlying wear patterns and the abnormal contact on the inner portion of the lateral femoral condyle. We know now this probably not the case.

In the past, a procedure called the “lateral release” was performed in which the lateral quad muscles were released in an effort to decrease this abnormal contact/ wear on the undersurface of the kneecap and ultimately leading to the softening of the cartilage layer. This has now been phased out and the lateral patellar tracking concept is no longer a valid theory with any of the rehab providers I know of personally. It has been replaced with a more current and researched concept (I’ll cover this in the next section.)

As of the time of writing this article (2018), the follow are Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome symptoms that will present on a Google search:

- Dull, aching pain on the front of the knee

- Worse with walking up or down stairs

- Knee pain with kneeling or squatting

- Knee discomfort when sitting with a bent knee for too long

- Mild knee swelling

- Sensations of grading or grinding when moving the knee

- Reduced strength of thigh muscles (long term disuse and avoidance)

- Popping or grinding

Many of these symptoms are correct, but I’d like to add some of the unique descriptions patient I’ve worked with have reported:

- It feels like pressure within the knee

- It feels unsteady

- It gives out for no reason

- I don’t feel confident on it

- It feels like it is full of air like a plastic bag

- Bending the knee fully feels like a ton of pressure

- The area around the quad feels tight (it’s actually a fluid sack under the quad)

- My other knee is starting to hurt as well (compensated motion)

- Pain at the beginning of the run and it tends to warm up in the middle of the run

- Very tender around the kneecap border after running

What’s the intersection point between Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome and other syndromes in this article?

If you go back to the section where I describe the biomechanical consideration to Hip Impingement Syndrome, you’ll see as the lumbar spine curve increases (arching the low back), we often see anterior pelvic tilt (butt out and sway back appearance). As the ilium (part of the pelvic ring) controls the femur bony geometrical stacking, the femur spirals inward throughout its entire length, including under the kneecap. Also to note here, insufficient eccentric control over internal femoral rotation from the gluteal complex can accentuate this inward spirally, which creates altered contact points between the kneecap and the distal femoral condylar groove (bone under the kneecap).

What cases this insufficient gluteal deceleration and control of the femur?

Some will say “gluteal amnesia,” and others will say the glutes are “off.” I personally never thought they actually “turned off.” I feel describing a “lack of full function” would be a more correct way of describing it. Vladimir Janda’s work focusing on the observation Lower Cross Syndrome describe this and even Dr. Stuart McGill observed this throughout his work with the spine and pelvis relationship, but it’s still an unproven theory.

Wrapping it up

Here’s a video I’ve made for all of the clinicians out there who’d like to understand more. Note: This was not created in lay public friendly terms. Enjoy!

As I wrote this article and made the correlated poster, I began to get questions about if any of my model was backed by solid research… and the answer is no. As of now there hasn’t been really any research to back many of the concepts we often use in clinical practice.

- Janda’s Lower Cross Syndrome

- Kelly Starrett’s Supple Leopard

- The Functional Movement Screen/ Mobility Stability Model

- Strength and Conditioning by Michael Boyle

- Strength and Conditioning by Dan John

Although some of these thought processes have gained more research backing over the years, most original ideas come as first a thought… validation through science follows far behind in the wake of a theory. I spoke with Dr. Andy Galpin PhD recently about if we should use unvalidated methods within clinical practice or should we only use all things validated through science.

His answer surprised me… he basically said ⅓ of what we use in clinical practice is research validated. The rest isn’t validated and probably never will because of the complexity of each theory. Humans are extremely hard to control within a research study and in research we are testing for one variable at a time to see their effect on a certain outcome. Humans have many uncontrollable variables, so the way each person responds to each methodology would be nearly impossible to validate (or at least you would never see a double blind RCT about it).

You can find his whole interview HERE.

The way you use this theory is up to you, the clinician. As a patient, you should understand the fundamental of this model just so that your eyes will be open to the probability that you’re “syndrome” shouldn’t be looked at under a microscope. Treatment and rehab needs to at least span to the joints above, below, and where your issue is, as well as your foot (since it’s the ground contact in closed chain human motion).

I hope you’ve all enjoyed the write up.

As I continue to learn or being disapproved in my theories I’ll continue to update this article. I’m a student to the process, I don’t know everything. If you have input to share please do!

– Dr. Sebastian Gonzales DC, DACBPS®, CSCS

Works Cited:

- “Running Injuries.” USAF Marathon, 2018, www.usafmarathon.com/running-injuries/.

- Lundborg, Göran, and Björn Rydevik. “Effects Of Stretching The Tibial Nerve Of The Rabbit.” The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume, 55-B, no. 2, 1973, pp. 390–401., doi:10.1302/0301-620x.55b2.390.

- Ogata, K, and M Naito. “Blood Flow of Peripheral Nerve Effects of Dissection Stretching and Compression.” The Journal of Hand Surgery: Journal of the British Society for Surgery of the Hand, vol. 11, no. 1, 1986, pp. 10–14., doi:10.1016/0266-7681(86)90003-3.

- Shacklock, Michael. Clinical Neurodynamics. Elsevier Limited, 2005.

- Langevin, Helene M, et al. “Ultrasound Evidence of Altered Lumbar Connective Tissue Structure in Human Subjects with Chronic Low Back Pain.” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, vol. 10, no. 1, 2009, doi:10.1186/1471-2474-10-151.

- Snell, Phillip, and Justin Dean. “Home.” Dermal Traction Method, https://dermaltractionmethod.com/.

- Ross, J. R., J. J. Nepple, M. J. Philippon, B. T. Kelly, C. M. Larson, and A. Bedi. “Effect of Changes in Pelvic Tilt on Range of Motion to Impingement and Radiographic Parameters of Acetabular Morphologic Characteristics.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine 42.10 (2014): 2402-409. Web.

- McGill, Stuart. Low Back Disorders: Evidence-Based Prevention and Rehabilitation. Human Kinetics, 2016.

- “Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalance.” Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalance, www.jandacrossedsyndromes.com/.